“…Elementary school is the highest level of education I have, and I haven’t mastered any valuable philosophies either since I was busy all my life working. Nevertheless, I’d like reiterate to all the young people, the boys and girls, who will one day run his country, that if you try your best with resolute belief in your efforts, the chance of success is available to everyone equally. Someone once said that ‘Time is a capital given to everyone in equal amount.’ A successful man is just one who has made good use of the ‘equal capital’ given to him, trying always to do his best, believing in himself” From the Chung Juyung’s Autobiography <Born onto this land>

The Great Star Underpinning South Korea’s Economic Growth The Life and Challenges of Chung Juyung

Chung Juyung was born

Chung Juyung was the one of the most famous Korean entrepreneur who known as the founder of all Hyundai Groups. He made a great contribution to economic development of South Korea. He was born during a time when Korea was under Japanese rule. He left many of significant achievements when South Korea gone through big moments such as independence, division and period of industrialization and globalization. Indeed, Chung Juyung personified the rags-to-riches story of the Korean economy. On Nov. 11, 1915, Chung Juyung was born, the first among six sons and two daughters of Chung Bong-sik and Han Sung-sil in Asan-li Songjeon-meon Tongcheon-gun, Gangwon-do. ‘Asan-li’, which became the origin of Chung Juyung’s pen name later in his life, is located north of Haegumgang Chongseok-jeong, the top of ‘the Eight Famous Locations of Eastern Korea’.

It passes Hwajinpo and Goseong, following the sea at the side at Sokcho. Chung Juyung’s father, who was the first son among the seven siblings of a poor family, was known as the ‘No.1 farmer’ who knew only one thing in life - labor. Observing his father, Chung Juyung learned how to fulfill the duties and responsibilities of the first son. His mother was also known as the best wife of the best farmer. She did twice as much work as others when she wove silk or weeded field. Young Chung Juyung followed his father into the fields even when he was very tired. He wanted to become a teacher when he graduated from Songjeon Elementary School after learning the joys of Chinese literature from his grandfather. But, as soon as he graduated from elementary school, his father wanted to make him into a No. 1 farmer just like him. He would carve out his own life without accepting his ancestral poverty as his fate. He left his house, hoping to work at a harbor construction site or at a steel factory, but he was caught by his father almost immediately and forced to return home. He tried again and again, but came back each time. After failing at his third attempt, he resolved to become the best farmer his father had always wanted him to be and live to care for his siblings. However, his firm decision was ruined by consecutive years of famine.

From a manual laborer to Rice Store owner

One late spring when he was nineteen years old, he left home for the last time. He got on a train to Seoul. His destination was Incheon pier. Life was difficult. He had trouble feeding himself by loading and unloading ships. Chung Juyung believed that he could enjoy a better life in Seoul by doing the same kind of labor. On route to Seoul, he worked in a farm house in Bucheon and carried stone and wood to a new construction site of Boseong College (present day Korea University) in Anam dong. He also worked as an apprentice in a rice candy factory for almost a year.

Chung Juyung looked for a job and soon found gainful employment at the Bokheung Rice Store as a delivery man. It was a stable job providing lunch and dinner and twelve bags of rice a year as salary. He learned how to ride a bicycle all through the night. More impressively, he learned how to balance the bags of rice on the bike itself. Within a few months he became the top delivery man of the store. Thanks to his faith in his work and his best efforts, he earned his boss’s trust enough to begin work keeping the store’s books – six months after being hired. And when his salary had increased to twenty bags of rice a year, he finally wrote a letter to his father. Needless to say, his father was surprised at his son’s sudden success.

Two years after he began working for the store, he received an offer to take over the owner’s job at the Bokheung Rice Store. The owner had been impressed by his unwavering diligence and faith in his work. On January 1938, together with regular customers from the former store, the 24-year-old man opened the Kyungil Rice Store. He began to develop a new customer base. His store prospered. It did not seem so unreasonable to say that the Kyungil Rice Store was on the road to become the best rice store in Korea. Around two years later, in December 1939, all Korean rice stores, including his own, were to be closed under the new rice distribution policy of the Japanese Government-General of Korea. That was the end of Chung Juyung’s Kyungil Rice Store. He closed shop and returned to his hometown with the money he had earned. There he bought two thousand pyeong of land (about 6,600㎡) for his father and married Byeon Jung-seok, the first daughter of the head of the town council.

Repairing cars : The Root of Hyundai

In spring next year, he returned to Seoul and found a business, to which he dedicated his life. Meanwhile, he took over a motor repair factory called “Art Service Garage” at the invitation of Lee Ul Hak, who was a regular customer and car engineer. Business flourished from the opening day, but just in twenty days, the factory caught on fire. Not only was the building was burnt down, but also five trucks under repair and an Oldsmobile. A lump of ash meant a lump of debt. Fortunately, Chung Juyung, who had accumulated trust, was able to borrow more money and began a motor repair factory in Dongdaemun. Art Service Garage drove on without stopping, continuing to offer quick and clear service. Though the factory was forced to merge with a Japanese company in 1943, he had acquired almost perfect knowledge of Pyeongtaek functions through his experiences in repairs. This became the motive for Chung Juyung to dream of becoming a leader in the automotive industry later. Not long after, his country achieved its independence.

On April 1946, one year after independence, Chung Juyung reopened his motor repair shop with the sign of ‘Hyundai Motor Service Center’ in the two hundred pyeong (661㎡) area granted to him from the U.S. military government in Korea near 106 Cho-dong Jung-gu, Seoul. Hyundai Motor Service Center became the origin of the name of the much larger company to come - Hyundai. This became the center for moving toward the modern age, making innovative advancements for the future. Hyundai Motor Service Center not only repaired cars, but also extended 1.5-ton trucks to 2.5-tons by adding a middle part and remodeled a gasoline car into a charcoal engine car. The best technicians all over the country rushed to the Hyundai Motor Service Center, expanding the company’s employee network by the year’s end from 30 to 80.

Hyundai Construction – The beginning of a legend

On May 1947, Chung Juyung, armed with the confidence from his success and the devotion to finish what he began, added another sign of Hyundai Civil Industries next to that of the original Hyundai Motor Service Center. In January 1952, merging Hyundai Civil Industries with Hyundai Motor Service Center, Chung Juyung founded Hyundai Engineering & Construction (HDEC) and entered into the construction industry enthusiastically. Chung Juyung had not been defeated by the sufferings of war, allowing him to jump head-first into the emerging market to meet the construction needs from the U.S. army during the war. When the then-U.S. President Eisenhower visited in the middle of the winter of December 1952, Chung Juyung showcased his wit – transplanting green barley to cover UN troops’ tombs with green grass after he received a nonsensical demand from the U.S. military, asking for UN troops’ tombs to be covered with green. When Seoul was reclaimed, HDEC was well positioned to handle almost all orders from the U.S. military.

Afterwards, Chung Juyung started postwar restoration projects rebuilding the country’s infrastructure, which had been destroyed by the Korean War. HDEC made rapid progress, performing multiple civil engineering projects and construction work, such as building roads, harbors, bridges, and so on, after the armistice had been signed. At that time, there was a dearth of experts and equipment, and Chung Juyung’s company booked huge losses for the restoration work of the Goryeong Bridge due to a severe inflation. Yet, he completed construction, accepting a deficit, but gaining credit for his hard work. Through this, HDEC built up a name for itself in the construction world, winning in 1957 a restoration contract for the Han River Footbridge, which was the greatest construction project of the time.

Building the Foundation of Nation and Industry

Chung Juyung’s motivation in taking Hyundai to the global stage was based on a philosophy he had developed during the Korean War. It was the recognition that ‘Hyundai is a company that develops together with the country.’

In the 1960s, large scale projects for economic development and industrialization began actively across the war-torn lands of South Korea. Building infrastructure was the first priority. Opportunity had arrived for his HDEC, which had successfully built the Han River Footbridge using advanced technology. Starting with the Honam Fertilizer plant, HDEC constructed the Korea Fertilizer and Chungju Fertilizer plants and increased its technological power by building thermoelectric power plants in Samcheok, Yeongwol, Gunsan, Incheon and Pyeongtaek. These successful constructions continued on with the 40m-high hydroelectric power plants at Chunchon Dam and Soyang Dam. Particularly impressive was Chung Juyung’s creative thinking, which he put to good effect in the design of the Rockfill Dam, for which he used gravel and sand, rather than making a concrete dam from sub-standard materials like cement and steel bars. The construction of Soyang River dam signified the company itself, standing tall, heralding the beginning of the new Korean construction industry.

The Gyeongbu Expressway linking Seoul to Busan was the largest engineering work in the nation’s history, forming the main artery across its territory. This mammoth project took just three years for completion. Most people believed that it was impossible to construct a 428㎢ expressway using the equipment and technology available then. Chung Juyung judged that reducing the work term through mechanization was the key to success and introduced heavy equipment worth 8 million dollars, a tremendous investment considering the state of the domestic economy at the time. Indeed, the total number of heavy equipment in Korea had been about 1,400, yet the heavy equipment introduced to construct the Gyeongbu Expressway numbered 1,900. On July 7, 1970, Gyeongbu Expressway, all 428km of it, was opened to traffic, meaning it was ready within 2 years and 5 months of breaking ground. This is still well-known to Koreans as ‘the shortest way made by our funds, our technique, our people’ in our history of expressway construction.

Chung Juyung went on to contribute to the enhancement of national competitiveness not only in infrastructure, but also in heavy industries, including the machine industry. His effort drove a transformation in the country’s industrial structure, which had been limited to primary industries like agriculture and light industry, leading the way for Korea’s modernization and economic development.

The Pioneer Who Paved a New Path

The Korean economy had been shying away from exports. The first overseas expansion, ‘the Pattani Narathiwat Highway’ Project of Thailand in 1965 was considered as an epoch-defining event. Opening up overseas markets was a new breakthrough in Korea, then, beset by a lack of resources. Lacking techniques, funds and equipment, no local firm dared to challenge international competitors. In Thailand, where West Germany, Italy, and Denmark had already entered, most of the equipment of HDEC (Hyundai Engineering & Construction) was conventional equipment used in domestic road construction. Though the latest equipment was purchased, they would break down often because operators did not know how to use them. Through multiple trials and errors, Chung Juyung himself made and operated vibration rollers, compressors, mixer and cars that loaded cement. Though they were rudimentary equipments, they became the starting point that allowed Hyundai to gain confidence in overseas construction. Afterward, winning and successfully completing projects like the Vietnamese dredge, the Alaskan canyon bridge and Australia's harbor construction, Chung Juyung prepared the foundation for earning big petrodollars during the Middle Eastern boom in the 1970s.

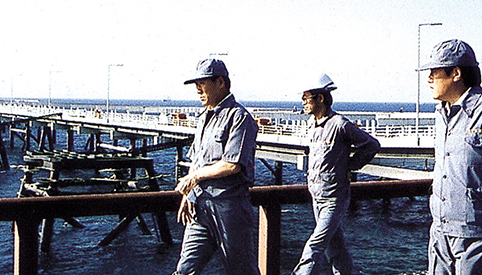

In particular, the order for ‘the Jubail Industrial Harbor’ of Saudi Arabia for $930 million received in 1976 was ‘the greatest public work in 20th century’. It was a big construction consisting of a lot of episodes, just like a drama, from receiving an order to the completion of the construction work. 2,500,000 man-days, equipment and materials were invested in this construction, making it the largest scale project since the Normandy landings in World War II. Chung Juyung surprised the world by his bold and creative ideas in transporting the steel-frame structures manufactured in Ulsan to the construction site in the Middle East by sea. The order received for Jubail Industrial Harbor was the biggest acquisition of foreign currencies in Korean history – about half of the national budget that year – and was a significant event that brought about a “Middle Eastern boom” across the industry, instilling confidence for overseas expansion.

The indomitable spirit of a businessman that pulled the country up by its bootstraps

Chung Juyung always worked in person to pioneer a new field in Korean industrial society, which had been severely damaged by the Korean War. He concentrated his efforts on building roads, bridges, dams, power plants and harbors as the basis of national economic development. At the same time, he pioneered the overseas construction market and opened the road to industrialize exports by initiating heavy industries, including the machine industry.

Chung Juyung in his lifetime thought of industry as a powerhouse to ‘make the country rich’ and ‘strong.’ With the belief that Korean industry should not create only wealth, he brought about a local revolution in advanced industrialization, fostering intensive shipbuilding, cars, heavy industry and steel to help make Korea strong.

It was also Chung Juyung that planted the seeds from which the image of Korea as ‘the world’s No.1 shipbuilding country’ sprouted. In the late 1960s, the Korean maximum ability of construction ships was at 100,300 tons on paper, but was actually only 17,000 tons through orders received from the U.S. Here, Chung Juyung threw down the gauntlet by setting up a shipyard that could handle hundreds of thousands of tons. Entering into the shipbuilding business represented Chung Juyung’s determination to develop Korean economic structure from its focus on light industry to heavy industry. The shipbuilding industry was an industry that could supply many jobs for people, though it was a big gamble.

In 1971, he left for England to obtain a loan with documents of a shipyard plan and only a single picture of the sandy beach of Mipo Bay. There, Chung Juyung succeeded in obtaining a $100 million loan by explaining to the banker about how Koreans excelled in building ships throughout history, showing him a 500 won bill on which the Turtle Ship was painted. He took orders for ships without actually having a shipyard and won a shipbuilding contract for two oil tankers totaling 260 thousand tons from Livanos, the Greek shipping magnate Onassis’ brother-in-law. With the ingenious idea of constructing a shipyard and building a ship at the same time, Chung Juyung was convinced that if you think outside the box, you can make the impossible, possible. Hyundai shipyard in Ulsan set a world record by simultaneously digging for the dock and constructing a ship. It achieved a feat unparalleled in world shipbuilding history: completing a shipyard in 2 years and building two oil tankers of 2.6 million tons at the same time.

Opening up a New Era for Korean Cars

The car was Chung Juyung’s first and foremost business goal. He foresaw that the car industry would lead in the future. He reasoned that ‘cars fly the national flag and are a measure of the nation’s industrial progress.’ Thus, he founded Hyundai Motor Company in 1967, which signed an agreement for assembling and producing cars with Ford, beginning the production of cars through a joint-venture company. But Chung Juyung dreamed of entering into foreign markets with Korean cars and sought to develop a domestic car that could compete globally. With Chung Juyung’s tenacity, the Pony, Korea’s first native car model, was completed in Dec. 1975. Without this step, Korea might still be known as an assembler, rather than a producer of cars.

In the early 1980s when the whole world was in the grip of depression from the Second Oil Shock, Chung Juyung decided to confront the crisis head on by developing an independent technique and promoted the so-called ‘X-car development project.’ This was intended for developing the unique front-wheel drive (FWD) model domestically and exporting it to the US, the home of the car industry. South Korea’s first FWD ‘Pony Excel’ finally came onto the world stage in 1985 and became a sensation in America and Canada, turning Korea into a car exporter.

In 1983, Chung Juyung decided to develop engines, the heart of a car and made a plan for ‘new engine development.’ He founded a laboratory, gathered talented people at home and abroad and sent them overseas to learn new skills. In two years, the trial product, Alpha Engine, was completed, raising the overall level of technological independence of the Korean car industry up another notch.

The seed Chung Juyung scattered became the strong oaks that would enable Korea to become what it is today, a strong auto-producing nation. Hyundai Motor Company began to travel the world starting in America, going on to develop various kinds of unique models. In 1998, it took over Kia Motors, and sought higher value in the Korean car industry through joint-growth. After this, Hyundai Motor Company and Kia Motors expanded their production corporation internationally and have now leaped into fifth place as a global car brand, selling over 7 million cars worldwide.

For Neighbors and For the Nation

During his lifetime, Chung Juyung emphasized the importance of returning companies’ profit to society. Chung Juyung believed, “When the scale of the company is small, it is an individual’s, but when the scale is big, it is an employee’s.” With such philosophy and belief, Chung Juyung founded in 1977 a public utility foundation, ‘the Chung Juyung Foundation’ with 50 percent of his own share of HDEC. At that time, Chung Juyung explained the reason for establishing the foundation. “I don’t forget workers’ efforts in contributing to the growth progress of Hyundai Engineering & Construction. If it had not been for the sweat and sincerity of our staff in completing difficult construction work in the coldest period of harsh winter and in the hot sands of the Middle East, we would not have seen such dazzling growth. HDEC wanted to return its profit to those who are lonely, poor and neglected.” The principle behind the Chung Juyung foundation is to ‘help the poorest neighbors in our society.’ It encompasses the spirit of humanitarianism in helping neglected neighbors in our society, performing social duty of an enterprise and overcoming the inequitable development of Korean society. The Chung Juyung Foundation has founded five large-scale general hospitals throughout the nation, including remote farming and fishing villages and has provided quality medical services ever since its creation. Also, it has been carrying out free treatment for underprivileged people who can not afford medical care and developing various projects to contribute to society, such as supporting social service agents for the old, children and the disabled, an academic research project to promote scholarly research and a scholarship project.

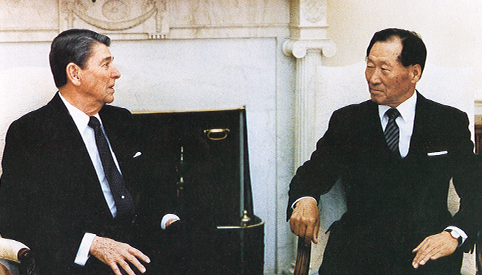

Chung Juyung has also demonstrated his particular style of leadership as a captain of industry in the world of finance, having been appointed as the CEO of FKI five times in the 10 years since he was first elected the 6th CEO of ‘the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI),’ a unanimous choice amongst entrepreneurs. In particular, following the 1978 Oil Shock when the world economic order showed symptoms of reorganization caused by the erection of trade barriers and multi-polarization, Chung Juyung emphasized that the economy should be led by private investors, rather than by the government, so as to advance the South Korean economy. During this period, South Korea’s economy not only grew and developed at a rapid pace, but also changed quickly into a free-market competitive system led by the private sector, rather than by the government.

It was through seeking to fulfill his responsibility as an entrepreneur that Chung Juyung set out to host the Olympics. South Korea applied to the IOC to host the Olympic Games in December 1980. At that time, no one truly believed that Korea would be capable of hosting the Olympics. Nonetheless, in May 1981, Chung Juyung became the Seoul Olympic Civil Chief. Less than half a year remained before the announcement of the hosting city. Nagoya, Japan already seemed within a whisker of victory, but Chung Juyung thought he had to complete the given work himself. Chung Juyung, like a bulldozer, jumped into hosting the Olympics Hyundai-style. First of all, he planned to hold the Olympics by making the most of the pre-existing facilities.

As the CEO of KFI, he called on the global networks of each company, including Hyundai. He met virtually everyone and did everything in his power to host the Olympics. He persuaded the 82 IOC members, including those from developed countries who had already announced their support of Japan, along with petitioning third world representatives from Africa and South America as well as the representatives from communist countries including North Korea. Finally, his trials gave birth to a miracle in Baden-baden, Germany, where the IOC Conference for selecting the Olympic host city took place. On September 20, 1981, the vote was Seoul, 52 – Nagoya, 27. Mr. Samaranch, then President of the IOC, announced the host city for the 24th Summer Olympic Games in 1988: “Seoul, South Korea.” The ’88 Seoul Olympic Games had over 13,000 athletes from 159 countries and was a place of harmony that went beyond all boundaries of ideology and race, where both East and West led by the US and the Soviet Union came together. It was post-war Korea’s fabulous debut on the worldwide stage. It was also a successful event that made a record profit of more than 350 billion KRW.

Chung Juyung began a large-scale land reclamation project. The Seosan Reclamation project developed farmland by reclaiming the sea. It’s fair to say that it was a massive task that changed the map of Western Korea forever. Construction was difficult, with the 200,000 tons of rocks under the sea proving to be difficult to reclaim for use in building a cofferdam due to a wide tidal range. Given this, Chung Juyung showed a novel approach in stopping the flow of water by sinking a 200,000 ton oil tanker that he had originally bought from Sweden to resell as scrap iron and then filling it in to complete the blockage. This method, now well known as the ‘Chung Juyung Method’, lowered the expected costs of construction by 29 billion KRW and reclaimed 104,047,410 ㎡ of land – an area 48 times wider than Yeouido.

Political Participation and Exchange Projects between North and South Korea

During his lifetime, Chung Juyung insisted that “politics and the economy should go hand in hand in developing the country, and the future nation should only manage, not rule.” In 1992, he chose to participate in politics based on this philosophy. For re-unification, it was necessary for both politics and the economy to be healthy, but in 1990 the national debt was seemingly ignored, in addition to the ailing economy. In these dire circumstances the ruling party cared only for maintaining its power via a three-party merger. Chung Juyung judged that the old politicians must not take charge of government management, and formed a new party, the Unification People’s Party. The party won 31 seats in the general election only after three months of its founding. Chung Juyung ran for president in the elections as the candidate of the Unification People’s Party in December that year and received 16.3 percent of the popular vote.

On June 1998, closely watched by the world, Chung Juyung crossed the Military Demarcation Line along with 500 bulls. It was exactly ten years since his first visit to North Korea. At that time, Chung Juyung was 85 years old. The visit with 500 bulls was a big event, charged full of symbolism that changed the Panmujeom forever, turning it into a place of compromise and peace, rather than the pit of steely confrontation it had previously been.

On October that year when he crossed the Panmujeom again with 501 bulls for his second visit, Chung Juyung met the North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, becoming the first private entrepreneur from South Korea to do so. A month after that, the Geumgangho – a tourist ship for sightseeing tours of Geumgangsan– took off from Donghae Harbor, heading for North Korea. On February of the following year, a land route to Geumgangsan was also opened. Chung Juyung’s projects aimed at North Korea were overwhelming both quantitatively and qualitatively especially in comparison to those that had previously been undertaken in the 50 years since division. As such, they became a decisive cornerstone for future North-South Korean summits.

A Great Believer in the Power of Positivity

Chung Juyung, during his lifetime, always emphasized, “If you look at the world brightly and clearly with a mindset of helping society, there is so much to do. Chung Juyung, who adhered to a philosophy of hope, laid the cornerstone for Korea to develop into a rich and powerful country by putting in place an industrial powerhouse and measures for peace. He went forward with the belief that ‘I have to’ and the assertion that ‘I can do.’ He proved with his life the tremendous tenacity humans can display through sustained action. Chung Juyung, who believed that ‘the main principle of everything is human,’ was a true humanist. He valued substantial experience more than knowledge. He was ‘a rich laborer’ who practiced the philosophy of sincerity and appreciation throughout his life.

Chung Juyung died on March 21, 2001. Mourners, regardless of societal class distinctions, came to the funeral parlor prepared in his house at Cheongun-dong. Going beyond notions of borders between North and South, the image of his upright and wise lifestyle still lives on in people’s hearts. He left with the message that “the most important thing is to live with a positive mindset. If you think everything’s possible, you can solve anything”. At the age of 86, Chung Juyung, passed away, but his dream lives on.